The United States of Literacy: A Look at the Early Republic’s Reading Habits

It’s easy to be pessimistic about literacy in America these days. We’re reading less than we used to, and even a cursory visit to this site will tell you that adult literacy statistics in the city of Cleveland are grim.

But there are reasons to be optimistic. As Jordan Weissmann points out in The Atlantic, younger readers are on the rise, despite the constant distractions of screens. Audiobooks are more popular than they’ve ever been. And that’s to say nothing of our over two hundred tutors volunteering their time at Seeds of Literacy!

As we approach our nation’s birthday, let’s take time to appreciate one more reason to have hope for the future of literacy: our past. America may have been, at the time of its founding, the most literate nation in the world.

In 1816, Thomas Jefferson made a memorable proclamation in a letter to a Virginia legislator: “Where the press is free, and every man able to read, all is safe.” The early republic came closer to that goal than just about any other nation of that era. According to education scholar John Taylor Gatto, literacy rates went as high as 98% in some of the Northern colonies.

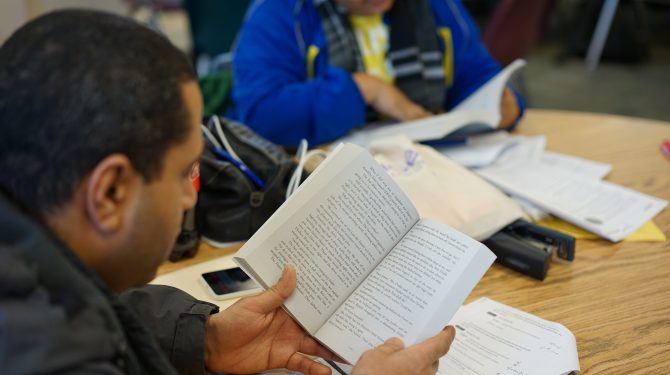

Those stats show it wasn’t just elites of the early republic who loved reading. Americans from the well-heeled gentry to the “contemplative workers” like weavers, shoe-makers, and farmers read frequently and voraciously–sometimes, as legend has it, even at the plow.

In terms of the ratio of newspapers operating to number of citizens, the early US crushed the competition. From the 1828 Journal of Education: “For meeting the intellectual needs of this 12,000,000, we have about 600 newspapers and periodical journals.” You couldn’t expect such a ratio from any European country at that time.

Let us not belabor the obvious point that colonial and early Americans lacked radio, TV, or any of the constant streaming entertainments we distract ourselves with today. It might give us better insight to focus on the intellectual acumen of many of our founding fathers, men of the Enlightenment who wrote prolifically: Jefferson, Franklin, Hamilton, Madison, foremost among them.

Media scholar Neil Postman calls America “the first nation ever to be argued into existence in print.” There’s plenty of evidence to suggest that the early American love of political pamphlets, from Paine’s “Common Sense” to The Federalist Papers, helped sway public opinion in favor of the Revolution and, later, the Constitution.

So as we celebrate our nation’s birth this week, let’s not give up on Jefferson’s dream of “every man able to read.” We’re working toward it, slowly but surely, at Seeds of Literacy. You can help.