Researcher Teams with Seeds for Eye Tracking Study to Determine Link Between Literacy & Predictability

WHEN WE READ, DO WE LEARN HOW TO PREDICT?

That was the question researcher Brittany Finch set out to investigate. The PhD candidate at Michigan State University specializes in cognitive science and second language studies.

If Brittany’s hypothesis is correct, literacy levels directly influence one’s capacity to anticipate words during listening activities. She’s also studying if people with lower literacy levels become faster at processing what they hear, even without predictive skills, when provided with additional instruction.

For her 12-week study, she collaborated with a literacy center in Kalamazoo, Michigan and a refugee center in Lansing, Michigan, but the bulk of the students for the 12-week study have been from Seeds of Literacy.

“Working with Seeds of Literacy has been absolutely amazing,” she said. “The students and staff have been nothing but welcoming and have gone above and beyond.”

THE PROCESS

Brittany conducted one-to-one sessions with students, explaining the study, carefully reviewing the consent forms, and gathering demographic information such as age, educational experience, and known learning disabilities.

After the initial paperwork, the student would complete a questionnaire about their language experience and how they feel about their ability to read, speak, and listen. Students are also given two literacy tests at the beginning of each session.

After that, the real work began.

THE EXPERIMENT

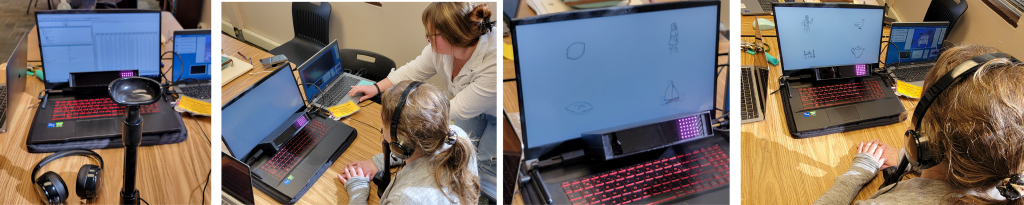

Utilizing the EyeLink Portable Duo (or eye tracker for short), Brittany monitored participants’ eye movements on a screen displaying simple line drawings paired with recorded sentences. The eye tracker registered participants’ gaze shifts towards corresponding images, particularly noting instances of predictive behavior. The study had two levels.

Level 1: Participants viewed four images simultaneously, each positioned in different corners of the monitor. For instance, images of an apple, a car, a cat, and a brick wall appeared while the audio stated, “Mary eats an apple.”

Level 2: Similar to Level 1, participants observed four images placed in different corners, such as a dog, a boy, a horse, and a cat, while the audio narrated, “Mary walks the dog.”

In the first level, only one of the images is food. Higher literacy levels would hypothetically predict the word apple after the word “eats”. In the second level, all four images walk. Upon hearing “Mary walks…” someone with a higher literacy level would presumably look at the dog before hearing the end of the sentence.

Each student is tested twice, once at the start of the program and again 10 weeks later to gauge any improvements. This testing involves the eye tracker and the literacy tests, so she can see the development of the students in both listening and predictive ability and reading.

EARLY RESULTS

“It’s really encouraging to see how invested the learners are in their development, and as a result, my study,” Brittany said.

Contrary to previous research suggesting predictive language skills emerge around grade six, her findings indicate that even seventh- and eighth-grade levels exhibit less predictive behavior than previously assumed.

Additional instruction can change that.

Brittany’s initial results showed students improved reading and even if they hadn’t shown prediction after the 10 weeks, their language processing speeds had gotten faster – even if they were just working on math during 10 weeks of tutoring.

“I hope that the results of my study will help students and centers know how much students are developing over this period of time, and give them insights into how this development impacts the students’ listening abilities,” she said. Additionally, she aims to shed light on effective instructional strategies that may benefit learners most.

###KLK